|

Season 3, Episode 13: “Midnight Riders” (Allan Eastman, director; Jim Henshaw, writer)

Bikers, dead dads, and incest. Just another day for the Curious Goods gang. KRIS’S THOUGHTS: The first, and apparently only, episode of the series without a cursed object, but not that much the better for it in terms of uniqueness. The planets are aligning, and a gang of biker ghosts (the Dragon Riders) returns for vengeance and possible ascendance if they can kill off their adversaries before the final alignment. It’s astrology meets John Carpenter’s The Fog. Plus ghost bikers? This should’ve been great! There’s a legend of a group of men wronged, and a priest and a number of townfolk who are responsible. Add the appearance of Jack’s father into the mix, and we have another relatively overloaded premise that leaves almost zero room for the Jack/Jack’s dad story, and leaves the legend little time to really develop. The Cheese: *Cold opener hilarity: Jack, Micki and Johnny are out in the night looking at the planetary alignment—and that’s not even the funny part. Jack and Micki are waxing cosmic, but Johnny is just … existing. [E: My favorite way for Johnny to be.] He does, at least, provide the episode’s opening and closing sentiment, a passing comet prompting him to say that his mom called them “heaven’s fireworks.” *There’s a little family resemblance in that Jack’s father seems just as fond of portentous pronouncements as Jack: “They’re wandering spirits, looking for the leader they left behind,” he says of the bikers. *The episode’s two “I think we’re alone now” lovers are confounded by their parents not wanting them to see each other, until they find out they’re (half-?) brother and sister. I can only imagine what Ryan would say if he were still around (and post-puberty). The Curiosities: We learn in another pronouncement from Jack’s father that the bikers were wrongly accused (of rape), hence their return for vengeance: “We killed them for what they seemed to be, not for what they were.” Yet what exactly were they? The current leader of the gang wears an “SS” patch on his jean jacket, suggesting this was no Harry Potter fanclub (though perhaps it was a J.K. Rowling one?) (too soon?). E: It’s never too soon for a sick Rowling burn. And yes, I noticed that too and talk about it below. The Goods: This episode is a welcome twist on writer Jim Henshaw’s usual race against time to close a demon-style portal. Another welcome aspect is the play with urban legends. To the tale of this episode’s “Headless Biker” legend, Johnny adds mention of “The Hook” and “The Hanged Boyfriend.” The “Hook” is one that Stephen King mentions, a legend told mostly to scare necking teenagers out of their wits (and back into their pants). Director Allan Eastman also directed the tight “Hate on Your Dial” (3.7), so the episode moves at a good pace. And it occurs in the brief span of a single night. E: It also gave me big time “Route 666” “Hook Man” vibes from season one of Supernatural. Perils of collaborating with someone in the midst of writing an SPN book; sorry about that. K: I’m always up for a SPN parallel. The Verdict: Despite two cool scenes—the biker gang bursting through the doors of the town church on wheels (and suggesting the bikers-in-church scene from Roger Corman’s The Wild Angels [1966]), and the buried biker leader later bursting out of the earth on his motorcycle looking a bit like Iron Maiden’s “Eddie the Head”—it’s another one of the series’ just-okay episodes. Dammit. ERIN’S THOUGHTS (before reading yours): I felt like there was a better episode lurking beneath the surface; another instance of the show being “good enough” but not striving for better. Because there were some great visual moments, particularly around the bikers (eg, the church scene) and that each act opened with the moving planets aligning, and some of the dialogue pointed at a particular self-awareness (Tommy’s crack about those “dorks from Riverdale”; the quintessential clean-living comic teens, right?). Plus, a “sins of the parents”, buried secrets story (where we even get a bit of Jack backstory!), and the shift of having no cursed object, should make for a much more interesting episode than this ended up being. Some of this was down to the narrative choices. You’ve got bikers showing up in town, as well as Jack’s dad (‘cause, sure, why not? [K: I’m with you; he could have been anyone.]) 17 years earlier, with the express goal of wreaking havoc. So, why is Cawley acting as if they are the innocent victims (“what they seemed to be is not what they were”)? I mean, they did beat up two teenagers for no reason except they were there. Obviously, the town’s response was horrifying, and makes the episode play like an homage to Nightmare on Elm Street (sins of the parents), but I’m not sure the suggested total exoneration Cawley implies with his statement is justified either. K: I was going to add the Elm Street connection as well; if this episode were really willing to explore this notion, it would have been built more clearly on parallels between the biker past and the return of Jack’s father. E: Also, if I found out that for months I’d been making out (or more) with my own half-brother, I would be so freaked out and disgusted and furious at both parents. I mean, that’s some Flowers in the Attic shit right there, and the episode really spends no time on it. (Perils of the semi-anthology, I know.) The cheese: Johnny’s It’s a Wonderful Life bit about “heaven’s fireworks” and angels, with the implication that Cawley has ascended. K: Again, Steven Monarque’s performative combination of “gee whiz” attitude and “oops, I farted” facial expressions lend themselves well to such hokum. E: PERFECT description. Another “meh” from me on this one.

Season 3, Episode 14: “Repetition” (William Fruet, director; Jennifer Lynch, writer)

A masterful Jennifer Lynch-written gem about accidents, atonement, and guilt. KRIS’S THOUGHTS: This episode is a sustained exercise in dread, starting with its gruesome opening, where award-winning columnist of the year, Walter Cromwell runs down a little girl out for a walk with her dog, and only the dog returns home. (Way to kill this guy’s buzz, Jennifer Lynch!) From the point at which Walter decides to hide the body, to the ending where he sacrifices himself so that all he’s done to thwart that initial death can be put right, this episode is a tightly constructed treatise on the power of guilt. Walter appears in the confession booth at least three times over the course of the episode, each time marking a point at which he is willing to take on increasing guilt, but only in the confidential framework provided by the Catholic church. [Erin, I suspect you’ll have a lot to say about this, as it’s the driving force of the entire episode.] Walter’s succession of bad choices is underscored by the cursed object itself, a cameo necklace (a gift from the girl’s grandfather we learn later) that he finds under the bumper of the car where he hit the girl. The cameo both gives a life for a life, and yet also dogs Walter with the voice of the latest victim trapped inside it, begging Walter to let their souls return to their bodies. Those constant voices drive Walter to distraction so that he loses his creative focus, his job, his will, his sanity, and ultimately his life. Erin: Hee! I always have something to say about that. And I didn’t say it below, but the Catholic element (I know it shows up in Protestant denominations more strongly, but we were here before you, so, suck it) beyond the overwhelming guilt that it suggests more subtly—and darkly—is that of substitutionary atonement. In essence, we have Walter and his victims as sort of an “evil” version of “dying for your sins” before Walter realizes he has to put himself on the cross, so to speak. Oh, and resurrection, obviously. K: As with several other of the cursed objects in the series, Walter’s use of it on himself (here intentional, but usually accidental in the series) breaks at least this “chain” of events so that the locket can be vaulted. How it gets to Micki at the Curious Goods store is one of this episode’s interesting innovations. A social worker who has met Walter in her homeless shelter becomes enmeshed in Walter’s story, and ultimately takes action to try to stop him. The social worker also knows Micki, and she unwittingly brings the locket to Curious Goods because of its ‘uniqueness’. The episode ends with a phone call from Jack, who’s away with Johnny watching “hot videos”... er, I mean, on a trip (see writeup for “Femme Fatale” [3.9]); the social worker overhears Micki saying that she hopes they’ve gotten the cameo before it does any harm, and the moment freezes on her shocked expression. The implication is that this might have become another recurring character on the show, once she’s been brought into the fold of secret occult knowledge the Curious Goods team has. I will say that this move would have been welcome, as the actress who plays Anne, Kate Trotter, is really wonderful. She also appeared in significant roles in “Quilt of Hathor” (1.19, 1.20, as Effie Stokes, the highlight of that relatively silly double episode) and the excellent episode “And Now the News” (2.3), both times as more villainous cursed object users, lending a kind of extratextual significance to her unwitting transfer of the cameo to Micki. The uniqueness here is that the episode shifts focus entirely to Walter’s extended guilt, and Anne’s attempt to help him and, earlier, the mother of Heather, Walter’s accidental victim who goes “missing” for the month that Walter has her body hidden. Writer Jennifer Lynch’s (writer-director of 1993’s notorious Boxing Helena) script is not only tight as a drum around its Catholic guilt theme, balanced by the selfless charity of a character like Anne; it’s also the only episode that reduces the Curious Goods team—here represented only by Micki—to marginal figures in their own quest. It’s a side story about people who would otherwise have been relatively ordinary. I would say that this uniqueness sets it apart enough for at least a mention in our book, but what really crystallizes this episode’s top 20 (and possibly top 10) importance is its pondering of the deeply moral stance of Friday the 13th: The Series. ERIN’S THOUGHTS (before reading yours): What a gem of an episode! Again, we have a “guest” writer (in this case) that barely touches on the Curious Goods team, which seems to be a feature of bringing in someone new. Indeed, Lynch may be the only one who almost completely sidelines them; Micki appears for fewer than five minutes, and Jack and Johnny are, of course, completely absent. Yet it shows so well what can be done with the anthology/semi-anthology format when you’ve got good writing and direction to elucidate the themes of not only a single episode, but the series as a whole. What really works here is that Walter is essentially a decent man; he writes a column that “looks out for the little guy,” cares for his ailing mother, and is hardworking (if a little boring). Indeed, the episode is almost entirely populated by decent people: the mother who won’t give up hope her child will be found, the physician who blames himself for Mrs. Cromwell’s death, the homeless guy who seems almost child-like in his trust, his fellow homeless friends who watch out for each other, even the editor who lays Walter off tells him he’s there for him if he needs him. And Anne Halloway, who only wants to help and does not judge those in her care, might be one of the most moral/empathetic characters we’ve seen. K: Yes, and yet played by an actor who has played two of the more reprehensible characters in prior episodes!] E: Nice catch; I missed that! It’s always been one of my narrative pet peeves to have a character in a book or film and series being described as a “good” person, merely because they are not actively bad. In that respect, the narrative and character choices Lynch makes here highlight this SO well. Walter himself, at the start of the episode, quotes his mother as he’s receiving his award, and what she told him about responsibility: “never turn from them; tackle them as best we can.” The episode proceeds to basically test that idea in a delightfully Poe-like “Tell-Tale Heart” fashion. K: A Poe reference. Bless you. And, yes! E: The cameo was one of those low-key effects that works so well! He fails at the first test; rather than doing the right—if difficult—thing of owning up to falling asleep and causing the accident, he buries Heather as if it never happened. It’s interesting that he doesn’t find the locket until he hears his mother’s voice calling for him, as if that awakened his moral sense. This may be one of the few instances in the series where the cursed object user isn’t drawn to it (or outright buys it), but rather draws itself to him. While it was obvious that the only way out for him was to sacrifice himself, that scene was suspenseful and moving. That he did it for one of the “little guys” he supposed wrote his column provides a nice parallel and suggests he’s not entirely damned. Also: two episodes of people waking up on the embalming table might be making me develop a phobia. The scene was horrible to contemplate, but kudos to the episode for acknowledging that is not a survivable situation, which makes Walter’s actions (to himself and the audience) all the worse. Other things: while we’ve never seen them before and will likely never see them again, I like the idea that Micki has a group of female friends outside Curious Goods. This may be one of the most female-centric episodes of the series (and what a sad commentary that is). The final freeze frame on Anne, where she appears to overhear Micki, was interesting; obviously Micki keeps that side of her life from her non-Curious friends, but Anne clearly knows something weird happened. Finally, this episode may say more about Lewis’s truly evil nature than all his cackling ever managed. The locket/cameo doesn’t really corrupt Walter; he is absolutely tortured by what he’s done, of which the object keeps reminding him and which will never be satiated. It browbeats him into damnation. In that respect, the homeless shelter offers a poignant symbol Lynch uses quite well: one mistake, one slip-up, and you could lose everything. I feel like I have more to say, but also that I’ve said WAY too much. Either way, this is going in my personal top 10. K: I’m with you on the top 10. You haven’t said way too much at all! Look at my write up for the next one, if you need to feel better about yourself. LOL. PS. One pet peeve: I was raised Catholic, and no priest I knew would deny absolution unless someone went to the civil authorities. It worked for the plot, but…. K: This just means the plot is less effed up than Catholicism. E: I mean, you’re not wrong. And it’s not entirely unbelievable; I could buy the priest telling him to go to the police—it’s a very “render onto Caesar” thing—but the denial of absolution was weird.

0 Comments

Season 3, Episode 11: “Year of the Monkey” (Rodney Charters, director; R. Scott Gemmill, writer)

The series displays its usual cultural sensitivity in an episode that borrows heavily from King Lear. KRIS'S THOUGHTS: This conventional story of a generations-old family curse (not the usual type of curse for this series) has a lot going for it, at least initially: It’s a combination of fairy tale, turning on lessons of greed and honor (and pride); it recalls (and I’m not kidding) King Lear with its ailing (kind of ancient) Japanese father testing his children’s honor and honesty with a set of Monkey statues “brought from the underworld to challenge man’s virtue”; and it has Tia Carrere, who isn’t any better an actress than I remember her being. Erin: Oh, you magnificent bastard! The Lear stuff was right there and I didn’t pick up on it. This English major hangs her head in shame. K: We’re not always looking for the same things! We later learn that the monkey trio, fashioned in the see, hear, and speak no evil mold has granted a kind of eternal life to their possessor, largely because he hasn’t found a single child among his children in many generations who is worthy enough to take on his financial “empire” (a word he uses). Thus, the explanation by one character that “The monkeys allow him to live long, if only he sacrifices his family to them.”Carrere’s Michiko, his only daughter this time around, proves worthy, but she impales herself rather than kill her father. With Jack, Micki, and Johnny canvassing different parts of the world to pursue the children who possess the objects as a way of testing them (and all this just to get their hands on one of Vendredi’s actual cursed objects), the goals of this episode feel a bit fuzzy. The three kids, two of them total greedy dicks, and the third a pretty cool woman who prefers suicide to standing up to a father who— let’s face it— has killed generations of his offspring (were they all that awful?) probably should have been the focus here, but there’s yet another narrative related to the family’s backstory about thwarted love that isn’t very compelling. It’s too bad, really, as the originating concept of a cursed object from another tradition could have been a nice variation on Lewis’s “I sold my soul to Satan” version. Even Wax is prompted to do a little digging into the origins of the three monkeys (2015, 398). Otherwise, she’s all logic questions, which this episode definitely begs. It’s filler for me—not good, yet not really bad enough for me to make a “see no evil episodes” joke. E: Right? It’s in that special “meh” category. For some of these there is a distinct feeling that if they’d given the scripts just one more edit, it could have been much better. It’s the sense of not trying hard enough that bugs me. ERIN'S THOUGHTS (before reading yours): I am always wary when a white show, with white directors and writers, sets their stories in another culture. I am not well versed enough in Japanese culture to know exactly how far off their portrayal of samurai culture was, but I’m pretty sure the three monkeys (and their powers) was wholly an invention of the show. And the “Year of the Monkey”? What is that supposed to mean, especially since (yes, I looked it up), 1990 was the Year of the Rat. It’s one of those: “Hey, let’s find some vaguely Asian thing and use that!” Also, how does Tanaka (Japanese) have two children who are Chinese (hi, Tommy from “The Tattoo”!; hey, it’s Cassandra from “Wayne’s World!”) and one who is Filipino? So, there was an interesting thread throughout the episode, of the father sacrificing his children for his own power that could have been far more resonant than it actually ended up being. Mushashi, too, was one of the first (and maybe only) person throughout the series who didn’t either disbelieve the Curious Goods team immediately, or ignore, or lie, but actually asked a really vital question: “Why should I believe you?” in response to Jack’s insistence that they were not gathering the cursed objects for evil. There is actually no good reason to think that they are trustworthy. K: Yes, that was a good moment! E: Finally, the monkeys go in the vault, rather than being returned to the temple they were stolen from? Oy. Is it really that hard to get these things right? Feh. Not loving this episode, I must say.

Season 3, Episode 12: “Epitaph for a Lonely Soul” (R. Allan Kroeker, director; Carl Binder, writer)

A cogent take on toxic entitlement, featuring a necrophiliac mortician—an episode both of us were surprised even aired. KRIS’S THOUGHTS: A number of the episodes of Friday the 13th: The Series have titles that don’t quite fit the subject matter (“Wedding in Black” [2.21] among them), but none so much as this misnomer, whose titular mortician Eli, while lonely, is about the least sympathetic cursed object user in the series. We open on a portrait of a forebear, here Neville Morton, founder of Morton Mortuaries, but the episode will turn on the actions of Eli, a solitary mortician whose loneliness, we learn, will make him susceptible to a cursed mortician’s aspirator, of which he comes into possession accidentally. Erin: Was it accidental? It did seem as if he was subtly drawn to it when he saw it in the back of his fellow mortician’s van. K: Maybe I meant coincidentally? Serendipitously? Certainly not fortuitously? The exchange between the driver of the death van that brings in a new “client” for Eli, along with the aspirator, which was apparently used to murder someone (either I’m not clear on these details, or the episode isn’t) is classic, offering the perhaps expected crass commentary of two men who deal in death as a business: “Just a kid. Motorcycle accident. It’s gonna take plenty of cedar and wax.” Eli initially seems sympathetic. As he begins work on the motorcycle victim, he remarks: “The mysteries of life, the universe … now, you know everything. Don’t you?” He then pops on some classical music and digs in. But, later, doubts as to whether this guy is a kind, thoughtful metaphysical ponderer who sees his job as a fine art, are confirmed by his decision to reanimate the 25 year-old dead wife of one of his clients because “All my life I’ve been alone, waiting for someone like you. Our destinies brought us together.” With so much to do in a 45-minute episode—getting Jack and Micki onto the scene as our intrepid investigators being primary among them—there’s no way the script could follow through on the perverse and disturbing implications of its main scenario. But what’s there is provocative enough. Eli’s resurrection of his new “bride” Lisa (the first of two in the episode) results initially in a kind of a living doll, a reanimated body with no will and no memory that doesn’t know what it’s doing, even when it embraces him. Eli consummates his new relationship with Lisa (whom he renames “Deborah”) in this state, the shades of abduction, rape and necrophilia disturbingly upfront in his actions. Will she spend the rest of the episode prone to the manipulations of perhaps the show’s most perverse cursed object user? No, in fact. She will regain some memory, recognize fiancee Steve just before Eli kills him and reduces him to ash, and ultimately decide to die in flames as the mortuary burns down. The moment alludes back to James Whale’s Bride of Frankenstein (1935), with Karloff’s monster intoning “We belong dead.” It’s no surprise that the moment will recall a classic Universal horror film, since director Binder’s script for a previous episode, “Symphony in B#” (2.5), evokes Phantom of the Opera and the later independent horror classic Deathmaster (1972). The Glenview Mortuary over which Eli presides is also a castle-like building left in ruins in the end. E: Ooh, star this! Clearly this is an element of Binder’s work! K: Totally. He’s one of the series’ best writers (and he also directs an episode or two).] The Curious / Goods: *The show airs in 1990, but again the date reads a year earlier. A sign of production context. *As Eli raises his second “bride” to a seated position on the gurney, her bones crackle. *There is a continual balance between the gruesome reality of death and the fragility of the body, and the spiritual accouterments we heap onto these things to deny them in the effort to find closure. The mortuary’s chapel with its open casket and artfully displayed body feeds into a corridor of clinical whiteness that connects the chapel to both the embalming room and the apartment where Eli lives. The fine separation between where we live and where we die is collapsed together here into a single space. *In the climactic scene, we have three women victims, and Micki manages to coax the newly resurrected second “bride” to release her from her constraints. Micki is able to save herself but not the two others, who, again, “belong dead.” *Director Kroeker notes that the effect of the aspirator plunging into the bodies of the living and dead in the episode had to be censored because one of the sponsors, an unnamed car company, requested cuts (in Wax 2015, 404). The Verdict Interviewed for the Wax book, director Kroeker notes that the episode is “all about the destructive folly of control” (403). Um, okay. It’s also one of the more “aware” evocations of that control relating to white male privilege. Here, the position of power over life and death, and the rights to a woman’s body, are all centered in Eli’s (and, if we include the cursed object itself, Uncle Lewis’s) horrendous acts. There is one last detail that fits this notion as well— that the cursed aspirator was ‘rumored’ to have been used first by mortician Nevill Morton himself, possibly to kill his own wife. E: Bringing in his work on “Ariel” would be really relevant here, as that episode revolves all around the way River’s body/brain was invaded/changed for the Alliance/Blue Sun to control her. K: Interesting. I just took a look at Kroeker’s work, and he did Dollhouse and Supernatural, and a bunch of other stuff, as well. This one may crack the top 25 for me. ERIN’S THOUGHTS (before reading yours): I did not expect to like this one as much as I ended up doing so. With the title, and the start of the episode, it seemed as if the episode was pushing sympathy for Eli. And yet, it really didn’t. If they’d wanted to garner sympathy, there are any number of tricks they could have employed: a brief flashback of a lost love, or a tragic accident (a la “Badge of Honor”). Instead, Eli comes off as super creepy from the start, with the possessive way he touched Lisa’s corpse. (Steve seemed put off by it in that first scene; as if Eli was grossing him out in a way he couldn’t quite define.) K: My cursor will battle your cursor for supremacy! Ahahahahaa! E: It’s Cursor Thunderdome! E: Eli was grossing ME out in a way that I could totally define. K: Hahaha. Word. And the way they attempt to recover him from the creepy-ass presentation in the rest of the episode (as you say next) just doesn’t work.] E: Never mind Micki’s assertion of Eli’s loneliness at the end “driving him mad”; that was, as I mentioned above, way more than the story as seen on screen suggests. I was surprised at how in no way did the episode shy away from the necrophiliac aspects of Eli’s behavior; the scene with Lisa lying corpse-like on the bed as he moved in on her was….yikes. For a Bush-era episode, the portrayals of Eli and Lisa, as well as Micki’s appeal to the newly resurrected Linda, showed a (sadly) surprising awareness of both gender dynamics and the reality of what this really was: a man who couldn’t deal with developing any kind of normal relationships, due to a desire for control. K: Yes! Smart. E: Yet, because neither Binder nor Kroeker even really hint at the reasons for it, it allows us to read it as not just Eli’s problem, but maybe a privilege problem. (I mean, how many episodes of this show alone feature men who do horrible things because they feel it’s “owed” them?) K: Again, we share the same brain. E: Micki’s “he’s going to abuse you” speech was absolutely on point, and Lisa and Linda embracing in the flames, choosing to be at peace, was moving. If there’s one aspect that didn’t quite work, it was Micki and Jack’s stubborn insistence that Steve was imagining things in his grief. (This may have been plausible in season one, but not at this juncture.) And yet it also kind of did work, because in an episode about control and gender, they basically “well, actually”-ed him. Steve’s “Don’t apologize for me,” was an interesting combo of Micki both dismissing Steve’s concerns/feelings and deferring to Eli. Finally, Allan Kroeker is actually a familiar director to me. Not only did he direct a number of Forever Knight episodes, but “Ariel” from Firefly, “True Believer” from Dollhouse, and “Faith” from season one of Supernatural. It wouldn’t be a bad idea to watch those eps again and see if there is a signature style…. K: I’d be into that. ;-) OH! I just realized that Kroeker also directed “The Long Road Home” (3.15). That’s a good one! E: Ooh, and it occurs to me that not only “Ariel” is about control, but also SPN’s “Faith” (a preacher’s wife controls a Reaper to give her husband healing powers and punish those she thinks are “sinful”) and DH’s “True Believer” is about a religious cult. This is definitely a top 20 episode for me. K: I do like it, and I am easily convinced on this one. I think that what might bump it out of the top 20 for me (if there isn’t room) is how much it’s trying to do, and the sense that it feels a bit overstuffed. The implications in the script are so large, it feels weird to not have them more fully, excessively explored. And then again, this is commercial TV, and we are at the mercy of the sponsors.]

Season 3, Episode 9: “Femme Fatale” (Francis Delia, director; Jeffrey Bernini, writer)

A 1940s film director gets off on his own creation, and the two guys of Curious Goods “bond” over some “hot videos.”

KRIS'S THOUGHTS: A little bit of Sunset Blvd. here, slightly flipped, with famous 1940s director Desmond Williams (a name that evokes that film’s Norma Desmond) bringing in the young ingenue to watch a film that will transport her onto the screen to die in place of the director’s beloved creation. Lilli Lita is the star of A Scandalous Woman, in which the heroine dies in the end, and she is also the director’s aged wife, an invalid sick in bed, largely (we presume) because she’s being gradually poisoned by her husband, who prefers the character she played to the person she now is. “As long as she’s alive I’ll never be free of that damned film,” says the younger femme fatale version of Lilli, thus establishing the logic of the cursed film print: if current Lilli dies, film Lilli lives.

The concept is fun, as is the episode. But I’m not sure it goes much further than this for me. For one thing, the actress who plays the younger Lilli, stuck in a femme fatale character from a film noir world, is only occasionally a convincing presence. Her successes occur mostly in the black-and-white film in which she’s “stuck,” saying juicy lines like, “I came for the only thing you can give me … a light.” In fact, I wish the manifestation of Lilli from the print were to appear in the show’s reality in black-and-white, as well. That would have been an extra reason for director Desmond’s wish for her not to be seen in his reality. Erin: Ooh, that would have been so cool. They may not have been able to manage that, technologically. K: I’m pretty sure they did something similar with the episode “13 O’Clock” (2.9).] Given that Desmond’s films were still being shown, hiding her away seemed ridiculous; anyone who saw her at the screening would have probably thought she was just cosplaying. E: I’d have to look it up, but it might have actually been a practical effect; ie, body paint and grey clothes. K: Micki, of course, gets trapped in the film, to live out its scripted scenario where the femme fatale meets her doom, gunned down at the end of a car chase. The climax of the episode runs parallel with this, played out in Desmond’s private screening room (where several others have met their fate). I love that Lilli shows up after Desmond tries to kill her by smothering her with a pillow: “Death scenes were always my forte,” she intones. Awesome! Though her subsequent lines are unnecessary and force a reading on the proceedings that isn’t necessary: “You said you loved me. But what you really loved was that pathetic coward that I portrayed. … I am not that slut you created for your movie.” More effective perhaps is Micki’s comment about being trapped in a genre film (or a semi-anthology horror TV series?): “I was completely at the mercy of everyone around me. I never felt so manipulated.” E: I actually wrote, “Way to go, Lili!” And yes, loved Micki’s line at the end. The Curiosities: *At the beginning of the episode, Jack appears after a long night “partying,” according to Micki. Jack says they were playing chess, but Johnny has told Micki they stayed up until 4:45am watching “hot videos.” I’m not sure what to make of this detail, on a number of levels, aside from the fact that it ties together the episode’s focus on the moving image and erotic desire. *Also, I guess this is partly why Johnny seems so resistant to seeing a film noir (in Johnny’s words, a film “they play all the time on TV”) with his new girlfriend. (Incidentally, if there were any more reason not to like Johnny, this works for me.) I’m glad his date ditched him. I’m also pleasantly surprised to see that Johnny’s date, who idolizes director Desmond, doesn’t become a victim of the cursed film print. I guess it’s because it wasn’t Ryan she was dating! E: Snort. Maybe Gen X Ryan will have greater luck than Baby Boomer Ryan; the curse that made him a kid cures his peen of death! The Verdict: Fun, but ultimately a bit inconsequential. Probably like having a sex date with Johnny. E: Hee! And yes, EWWW on the idea of Jack and Johnny watching porn together. Is that a thing straight guys do? K: It is. As a queer guy, I find it totally hot. But maybe not so much with Jack and Johnny. E: Hee! I get to learn something new every day! ERIN'S THOUGHTS (before reading yours): I’m not sure it’s possible (and certainly not by 1989) to have an episode about film or television and not have it be even a little metatextual. Certainly they did here, from fun little Easter eggs to the more serious thread of Desmond’s use of young women to feed his fantasy (and thereby literally destroy them). I appreciate it when it’s clear the writer did his or her homework: Desmond’s “A Scandalous Woman” says it was released by Paramount, who, of course, co-owns CBS (which produced and aired Ft13th: TS), but it was also known for its noir output. There’s also a fun little Easter egg in the opening credits of the film; it lists “Frederick Mollin” as the composer of the film score; indeed, Fred Mollin is the composer of the series’ score. What I found really fun (and a bit subversive) was the Sunset Blvd.-ness of it, down to naming the main villain Desmond. K: Yes! Although his name should have been Norman Desmond, to riff on both Sunset Blvd.’s Norma Desmond, and Norman Bates. E: Old Lili may wear the turban, but Desmond is the real out-of-touch diva here. K: Haha, totally. E: Gender-swapping the one who felt like “it was the pictures that got small” and retreating further and further into his own fantasy allows the episode to say some pretty on-point things (at least for the late 80s) about power and control. Older Lili has accepted that she has grown older and changed; Desmond has not. He needs constant attention and adulation (as did Norma). The real surprise, however, is Film Lili’s realization and assertion of her own autonomy, and being enraged at how he objectified her and diminished her contribution. “You’re mine! I created you!” (Pity it’s followed up by her dying due to exposure to horrible special effects.). There’s a deeper point to make about the predatory nature of studios/directors/producers and the actors/actresses they too frequently used, abused, and discarded. Micki’s “I felt so manipulated” while in the film is both apt and could be looked at as a commentary on how the show treats Micki overall. K: Yes, I say the same thing above, as you know. We share the same brain sometimes. Sin: Vanity. Verdict: Fun (so much better than the last one) but with surprisingly deep moments. PS. Geez, I can count on one hand the amount of characters named “Erin” in films or books or TV shows, and I had to get the whiny one who thinks noir is romantic? GRRRR. Still, she was smart enough to ditch Johnny.

Season 3, Episode 10: “Mightier than the Sword” (Armand Mastroianni, director; Brian Helgeland, writer)

A smart take on true crime, celebrity, and the lust of retribution, with the incomparable Colm Feore.

KRIS'S THOUGHTS: This episode is tightly constructed and deftly written around the fascination the general public has for serial killers. The cold opener (quite long at 6.5 minutes) nails the complexity of this, with its group of protesters outside a prison having a tailgate party with ice-cold beer to support the death of a killer. “Die, Fletcher, Die! … Gas him, gas him, gas him! … Time’s up, buddy!” (Side note on a little inconsistency: Arizona, California, Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri and Wyoming are the only states that use the gas chamber, placing this episode’s events somewhere not where the shot takes place.) Colm Feore plays Alex Dent, a crime biographer who uses the cursed pen to turn innocent people into killers whose murders he turns into bestselling true crime books. It’s a smart concept. Feore is an excellent actor, conveying the cold cruelty necessary for his particular use of the cursed fountain pen. Dent’s best line (outside of the juicy passages he writes) is directly related to his wicked greed. After rendering a priest an eventual killer with his “poisoned pen,” he intones: “He’ll be more than a new man; he’ll be a bestseller.” Erin: He was SO good! K: Micki, who will become Dent’s final victim, inadvertently sets herself up for the victim role when she intones early on, “Serial killers aren’t my idea of a good read.” Reluctantly, she attends a talk by Dent with Jack and Johnny (who, we’ve learned in a prior episode, is a budding writer of trash—his source of inspiration is a publication like The National Enquirer or Weekly World News). At the talk, Dent’s “Evil is a disease” thesis is an interesting comment considering that the pen requires the transmission of fluids. (This is the 80s, after all, and anxieties around the Reagan-denied HIV-AIDS crisis would still have been rather high.) Dent advances evil as a biological process, a disease. And considering his cursed pen requires blood, a blood he writes with, the metaphor is compelling, even as the HIV-AIDS context makes the idea of “evil” biological transference deeply problematic. It’s interesting here that the cursed pen allows Dent to create his own true crime serial killer narratives using real men (and eventually Micki) as his “protagonists.” The brother of one of Dent’s victims who has an outburst at his talk (“You glorify serial killers!”) notes as much. But on a more nuanced critical level the episode suggests that true crime books do in fact manufacture the kind of fascination that, if it doesn’t create serial killers, certainly centers them and not their victims. The man at the talk says, “You didn’t even know my brother!,” here perhaps inadvertently tagging the notion that true crime almost never focuses on the victim, despite the fact here that victim and victimizer are at least partly one and the same. The Goods:

The Cheese, the Beautiful Cheese: *I love the scene with Marion, Alex’s estranged wife, watching the news conference in curlers, plotting blackmail, and putting out her cigarette in her coffee. *Another scene where the Curious Goods team is allowed to wander onto a police operation scene—this one where Dent is poised to meet the killer. They lose Dent when he unplugs his wire, and yet Johnny and Jack are allowed to lurk in the background. * The address on Micki’s driver’s license: 666 Druid Ave / Hilldale, USA / 90039 (a Los Angeles zip code). *The artist’s rendering of Micki as “female slasher” pictured on a TV newscast is fantastic! (See image below.) I hope Robey got to keep it. *As they break into Micki’s murder of Dent, Johnny’s line to Jack, who has the pen: “Pull the evil from her neck!” The Verdict: One of the better ones, top 20. ERIN'S THOUGHTS (before reading yours): Pardon the pun, but that was definitely more than a few cuts above the usual episode. In some respects, it’s touching on the same material as both “Poison Pen” (the writing implement that lets you control others) and “Double Exposure” (guy gains popularity through creating the crimes he reports on). Yet the blend actually transforms the material here into a highly enjoyable, beautifully cheesy episode. There is an element here that initially seems to suggest to me, as a child of the 80s, the PMRC [K: I don’t catch the acronymic reference!] [E: Sorry! It stands for the Parents Music Resource Center; it was headed by Tipper Gore and claimed bands like Ozzy Osbourne and Judas Priest were corrupting kids’ minds. It’s why we still have “Parental Advisory” stickers on music releases.] [K: Ah, yes. I remember Tipper’s righteous campaign. I never knew it was called that!] stuff: that violent imagery, books, or music lead to violence. (Just one of the innumerable ways the 1980s were “1950s: The Sequel”.) I say suggests: Jack straight up says it with regard to Billy/Alex, that writing pulp novels made him violent. Yet the rest of the episode seems to undermine that reading. It isn’t just him; from the very first scene, the writer/director seem to purposefully suggest Alex is tapping into the general bloodlust of the population. I absolutely love the cross-cutting between inside the prison walls and outside, where the crowd is shouting “Gas him!” while drinking beer and dancing. (A little close to the current reality.) K: Agreed. Mind-bending, that. E: That Alex monetizes and gets off on it doesn’t make the others’ behavior better. (And to go full Freudian for a minute: “get off on it” is exactly how it’s shot, as he sweats and stops and rubs his sore hand. Yup.) K: Get yer mind outta the gutter! (Also, agreed.) E: Hee! Never! The plot here moves fast and the dialogue is crisp. Not once did my attention flag; this was a remarkably well-constructed and well-written episode. Too many times it’s glaringly obvious what the cursed object does, and thus makes the Curious Goods team look slightly idiotic for not getting it right away. But this wasn’t entirely clear at the first instance, and it remains slightly mysterious at the end. (In a good way.) Was there a first killer Billy met with and jabbed with the pen, or did Billy/Alex make the first one, and then continue to “create” them? It suggests the “disease” metaphor quite well, with Billy/Alex as the vector and the pen as an infected needle. (As an AIDS metaphor, it’s both subtle and not subtle, but the conflation with “evil” is troubling, to say the least.) Robey did a pretty good job with the empty-eyed serial killer bit [K: Agreed. I love her performance.], and I loved the connection to the slasher genre not only in Alex’s naming of her, but the final jump scare at the end. For once, the episode doesn’t hand wave the negative/lasting consequences of the work. Of course, the real gem is Colm Feore’s Alex, who brings the same intensity he had as the ballet maestro in “The Maestro” (2.23) to Alex’s smirking “king of sleaze.” This is a top 20, if not top 10 for me, even with the clear green-screening during Micki’s breakdown. K: It has to be intentionally unreal. There was no reason for this except to suggest a destabilizing of Micki’s reality. I see it as a conscious choice to turn a familiar space, the Curious Goods’ overstuffed display floor, to an uncannily compromised space of off-kilter nightmare. E: I meant to say above: I really like your take on this!

Season 3, Episode 7: “Hate on Your Dial” (Allan Eastman, director; Nancy Ann Miller, writer)

An interesting—if deeply problematic—take on toxic families and the persistence of hate.

KRIS’S THOUGHTS: At its most political, this show is disturbing and important. In this context, this episode is the first from season 3 worthy of discussion at length in our book. It’s equally as political as writer Nancy Ann Miller’s previous effort, “Wedding Bell Blues” (2.22), but dramatically different in tone. It’s also more problematic in what it’s trying to do.

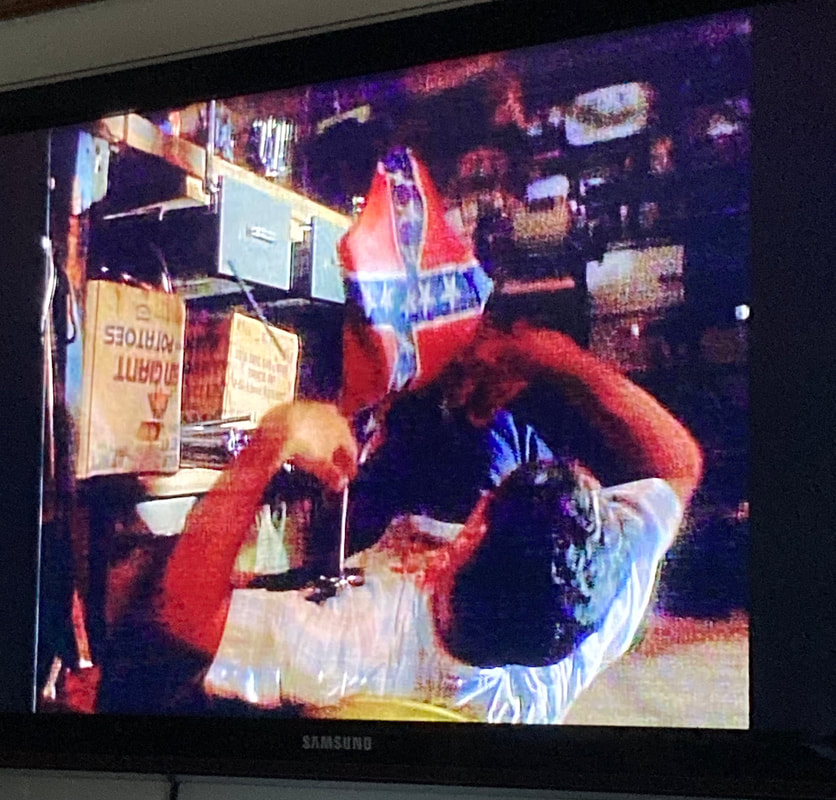

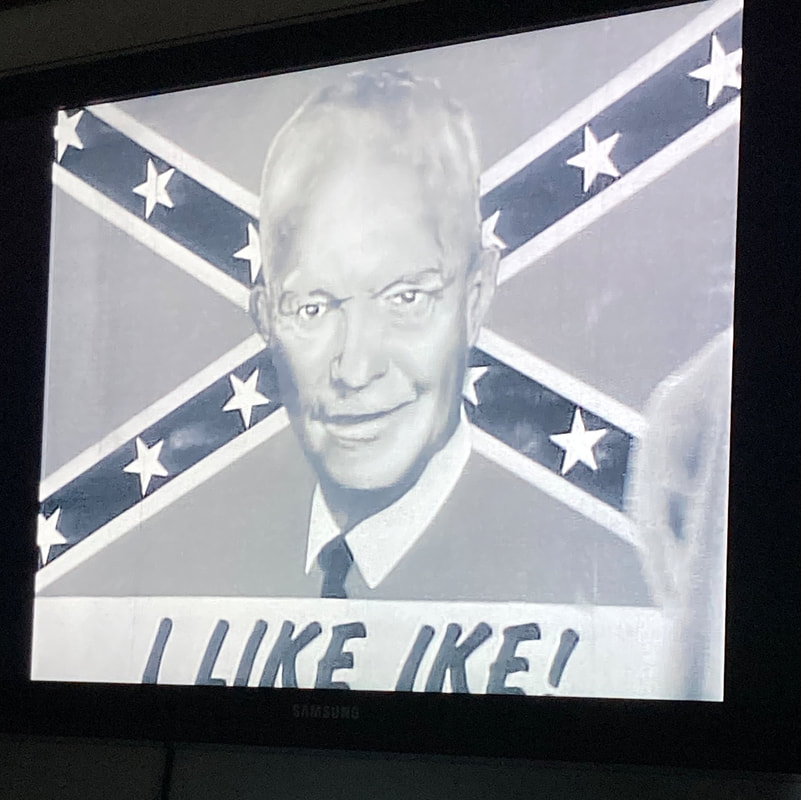

The cold opener features a scene in a garage between brothers Archie and Ray Pierce. Archie is noticeably “slow” (a word used in the script; Johnny’s word for him later is “retarded”), and Ray is noticeably a racist pig, longing for days past in Mississippi when their daddy was in the KKK. Daddy was later hanged for killing a black man, leaving only the two boys and their mother, a young actress wearing old-age makeup, suggesting clearly that this will be a flashback episode. The boys are working on a white 1954 Chevrolet in this scene that will figure pivotally later when Johnny accidentally sells a cursed factory-made ‘54 Chevy radio to Archie (adding in a confederate flag that just happens to be in the Curious Goods shop as a bonus). Curiously (ahem), the radio comes to the shop when a Black woman brings in box of “junk.” for this viewer, at least, the suggestion was that this could be a case where the radio’s “allegiances” are to a cause that is not necessarily that of the owner, which would have made this episode in some ways more trenchant in its investigation of racism. I’ll explain. In the episode “Crippled Inside” (3.4), the so-called benefits of regaining sensation in her body ultimately result in the protagonist’s moral corruption and rather tragic death. In “Hate on Your Dial,” the radio gives Ray what he desires: to return to a time and place where his vicious racism could be more out in the open. (Of course, he could have waited for the Trump era for this.) But the “tragic” ending for Ray—burned at the stake as a spy at a KKK rally by his own father—is inadvertent. Had the radio transported Ray back to 1954 actively as a way to punish him, rather than fulfill his desire to be freer in his hate, the episode might have a different edge in its entirely white-centered narrative. At least, in other words, there would be at least a centering of Black agency in the cursed object itself, which would offset the episode’s problematic discussion of racism’s degenerative effects on white families. The question is, can this episode push past its white-centering? The answer is, unfortunately, no. The script refers to Black Monday, “the day all white folks got in trouble,” possibly a riff on the more typical use of the term to indicate moments of stock market crashes and ensuing economic depressions. And in keeping with the sidelining of this once-mentioned event, we see nothing of the black families affected, just Black victims being persecuted by hooting and yee-hawing white folks. The “tragedy” here is one of how racial hate tears apart white families, and the episode ends with Ray’s father burning him at the stake thinking him a spy, and on the final image of Mrs. Pierce in tears holding the photo of her family. Erin: Yes! Like the previous episode, it’s privileging the wrong pain. K: As he and Jack drive “back to the future,” Johnny’s last line is, “I can’t imagine what it must have been like being black here.” And that is part of the problem: neither can this episode, which doesn’t do anything to center that reality, instead electing to unsettle whiteness. And yet it does unsettle white viewership. An early flashback scene in a diner plays out like a stage, with a Black man touching a white waitress and ensuing violence watched by the white patrons. The white TV viewer will likely feel their own positionality in this uncomfortable scene, but how is a Black viewer meant to be addressed here? Their discomfort comes from being aligned (yet again) with victimhood. The early scene in which Ray torments a kind and friendly young Black kid—making him dance to flying bullets in a basketball court—and then shoots him in the back while he crawls away is an all-too-familiar image, then, now, and in the past. The episode centers the past, but the Rodney King riots are just two years away (29 April to 4 May, 1992). Jim Henshaw, Executive Story Editor for the series, marks this as the series’ best episode, but I would suggest it might instead be the series most exemplary “best intentions” episode. While it handles the subject of racial hate head-on, it fails to situate this experience at all with the perspective of marginalized people, who exist as figures to support a tragic narrative of degenerate whiteness. And yet, taken in the context of the whitewashed, amnesiac, denying Reagan era’s “Morning in America,” the episode is doing some important things. For one, this is the most fucked-up twist on Back to the Future (1985) that I could imagine, and it almost is a critical lesson in what could have been done with that idea instead of revisiting the 1950s as some sort of nostalgia trip. (“Time travel back to a frightening future …” intones the episode promo.) Ray meets his own mother, pregnant with him, and comes to learn that his father’s racial hate is accompanied by acts of violence on his own family. The question of the witness that puts Ray’s father away for murder is never answered, and yet it has to be Ray Pierce’s mother. She’s a silent sufferer in the present, and a silent witness in the past, to discussions of the crime in the family home, and to her husband’s violence with Archie (to stop him from chanting, “Daddy killed a Negro” over and over again). It seems she will act as a witness in part to get him out of the house, and in part due to her conviction that Black folks are “just people like us,” which she says to the grown version of her son, Ray, in the past—again, while he’s gestating in her belly. The fact that Archie in the present narrative is an ally of marginalized folks—telling Ray at one point that he doesn’t like Ray’s violent treatment of his Black friend, Elliott (the boy whom Ray later kills)—is as much an act of resistance to an ideology of hate as his mother’s turning witness against her husband. E: It’s the smallest flash; while Ray is burning, the episode briefly shows what is going on in Steve’s head; he hears Ray saying “there’s a witness” and he sees his wife. He knows who will turn him in. K: In a bit of foreshadowing of similar family violence, at around 29:15, Ray bludgeons Archie to death with a ball peen hammer. As Archie falls to the floor, the confederate flag falls with him. The image (below) would make a compelling screenshot for the book. Another interesting image follows just after, when Jack and Johnny are transported back with Ray to 1954, as Ray rushes to escape the murder scene. As Ray tears off into town, Jack and Johnny stand in the middle of a country road in front of a giant billboard of a smiling Eisenhower backed by the confederate flag and the familiar tagline, “I like Ike.” There are other significant details in the episode that feel rather characteristic of scriptwriter Miller’s previous satirical gifts in “Wedding Bell Blues,” and that undercut some of the episode’s earnest white-centering. One comes in a visual motif that features the town sheriff always sweating. Later, arriving half-heartedly to break up a white protest of Black lawyer Henry Emmett’s efforts to bring justice, he also mentions the sweltering heat. For all his confidence and bravado, he’s “sweating it.” Everything the sheriff says to Emmett as he quells the protest reads like a warning, something Emmett confronts him with. It comes as no surprise, then, when later a captured Jack observes that one of the KKK members has the same shoes as the sheriff. In another such detail, following the protest, the moment where Jack’s friendly warning to Emmett ends in his being thought of as a KKK member is on point: “Thank you, sir,” says Emmett. “I have to say that I’ve never been intimidated so politely.” At least the script doesn’t let Jack come off as a white savior. In a later scene in the final 1954 segment, Ray comes in after Archie has been beaten by his father, and he doesn’t even ask until well into the conversation while Archie is on his mom’s lap badly injured. Here is Ray, after having killed his own brother in the present, looking upon him, brutalized and abused in the past, by a father that will later burn Ray himself at the stake, Ray pleading, “Daddy don’t!,” as his face burns off. E: What’s even worse? He HEARS Archie being beaten and actually fucking shrugs and drives off. BURN HIM.

ERIN'S THOUGHTS (before reading yours): Well, this was brutal to watch, although it taps into what went fairly unacknowledged at the time this aired; the Boomer second wave, of which Ray would be a part, were frequently just like him. (Witness, as per example, Randall Terry, the guy who started Operation Rescue.) These are the Boomers that missed out on the economic boom of the 60s and came of age in the 1970s. They generally were super pissed off and blamed everybody except the ones that were actually responsible. Ray fits this mode quite well.

(The episode also takes a page from, in my view, The Twilight Zone movie section “Time Out,” particularly the fate of the bigoted “time traveller”.) K: Interesting. The ill-fated one with Vic Morrow? There is also a segment of Rod Serling’s Night Gallery that does this kind of thing better than anything I’ve ever seen on television, before or since.] E: Oooh, want to see! And yes, the Morrow one. K: It’s in the series pilot, the last segment, called “The Escape Route,” about a Nazi in hiding in South America. E: I found this episode extremely difficult to watch. The whipping/beating scene went on for too long; I had to fast forward. There is a line—at least for me—between what serves the narrative and what becomes gratuitous. The mention of Roots in the episode is instructive; having aired maybe 10 years earlier, and containing scenes of abuse such as were shown here. At the time, that was groundbreaking, and given that Alex Haley wrote the source material based in part on his own family history, it has a different resonance. Because the episode stays firmly in the point of view of the white characters (even those with good intentions), the violence it shows becomes even more problematic; we don’t get the perspective of the victims at all. Even the fact of having Archie be a stand-in for the other marginalized people (and hands-down the most sympathetic white character) doesn’t quite push it into “white savior” territory, but still privileges the white perspective in a story about racism. K: On point. E: There are some things that this episode absolutely nails. One, that you can’t tap into that rage and expect it’s not going to be enacted against anyone who gets in your way. While this seems obvious, clearly the writer understood the psychology of that time of person well enough to show that no one was safe from it; poor Archie. Even better? Unlike “The Shaman’s Apprentice”, when Henry Emmett (that last name cannot be accidental) tells Jack that it was the most “polite” intimidation he’d gotten, Jack’s first instinct ISN’T to try and “not all white people” him. He reads the time and the situation exactly right; there is no way that Jack, no matter his intentions, can communicate that information to Henry without it sounding like intimidation. K: Agreed. And, funny that the same humility and comprehension could be given to an Indigenous person in “Shaman.” E: That the sheriff was complicit was expected; that he was in the Klan and responsible for burning Ray and attempting to do the same to Henry was a bit of a turn. (Not sure this qualifies as a plot hole, but if the sheriff is in the Klan and is himself guilty of murder, how did Steven ever come to trial, never mind being convicted and hanged?) The constant use of the word “boy” directed at African American men of all ages. Finally, that racism isn’t “solved” or a product of the past. “The future isn’t much more comforting.” Jack, you’ve no idea. K: It’s quite a different voice here from Ryan’s notion in “Eye of Death” (2.13) that “in my time, no one thinks badly of” the confederacy. And yet, that these two statements can come in the same series suggests a very messy and unformed series politics, mostly conservative with the occasional blip of subversion and critique. This episode is almost a capsule of the rest of the series in that respect. E: This, I think, is a significant issue with the anthology/semi-anthology format overall, and the era. Excepting Lear and MTM Productions, the era of the “showrunner” was more than a decade later. There’s no real sense of this as a “Mancuso” production, so it is the writers/directors who set the narrative and visual tones, rather than having an overarching POV that is typical of showrunners now. Add that to the lack of a strong arc and it makes it indeed makes it messy and hard to pin down. K: This makes me think it might be a good idea to take a look at the most truly subversive episodes, and locate the more critical voices (writers, directors) on the show. We could even do a separate list of top ten “most subversive/political/edgy” episodes. I’m not sure this one would make the cut, solely for its white-centering narrative. We could make a “Nice try” list to compliment it! E: I LOVE every part of that idea. I think it makes the most sense in approaching these types of shows; it should have occurred to me before, but I’ve gotten so used to that particular paradigm that it didn’t. Not to veer too far off, but Caldwell’s Televisuality is a good read for this, particularly when he talks about the zero-style aesthetic of TV in the 1970s which prized the writing/acting over the visuals. It’ll take some digging, I think, but I think focusing on individual writers/directors is already kind of baked into what we’ve done here. I also was surprised by some of the plot turns. I’d figured out that Margaret was probably the witness about the halfway mark, and figured that might be a turning point for Ray. Instead, he never figures it out, and dies horribly. (Am I sad about that? No. Does it trouble me that it doesn’t make me sad? A little. K: It’s hard to be sad because the episode’s centering of whiteness is so troubling, you feel like you’re forgetting to be outraged by that, if you’re sad for Ray. E: That Steven was responsible for what happened to Archie also surprised me, and the way in which Ray mythologized his father would lead where it did was exactly right in terms of his character. The way this episode resonates with what’s happening today makes it a chilling watch, from the mythologizing of the past to the fact that the “radio” is a conduit to enacting hate is a subtle touch from a show that’s rarely subtle. K: Interesting, yes. And connects to “The Butcher” (2.19) with its radio show, and, to a lesser extent, “And Now the News” (2.3). The radio gets a lot of “airtime” on this series. I’m about to watch “Spirit of Television” (3.18), so we’ll see where that one takes us.]

Season 3, Episode 8: “Night Prey” (Armand Mastroianni, director; Peter Mohan, writer)

The introduction of a community of vampires plays fast and loose with the show’s mythos, pushing this one into backdoor pilot territory.

KRIS’S THOUGHTS: In this episode’s cold opener, a pensive, melancholic Jack sits on a boardwalk bench at night, musing on the blurring of distinctions between good and evil (his words are quoted in full in Wax [2015, 370]). It’s a scene in keeping with the times, with the romantic vampire popularized by Anne Rice (1976) now at the height of its popularity. The decade began with John Badham’s (1979) sexy Dracula played by Frank Langella, and the TV series Cliffhangers’ (1981) Dracula played by Michael Nouri. And Interview with the Vampire (1994) was soon to come. Intimations of Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003) come as well with much of the action taking place in a post-industrial warehouse space where vampire hunter Kurt has holed up in an attempt to reclaim his fiancee, kidnapped and turned years before in 1969 by hot vampire Evan Van Hellier (A vampire stole my bride!).

Bonus note on the cold opener (and one later scene): Conventional populism would suggest the opening scene of two ill-fated lovers being stalked by a vampire be underscored by Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata”; yet, here, a pleasant surprise comes in the use of music used by Stanley Kubrick for a morose ending scene in Barry Lyndon (1974) (it’s Piano Trio No. 2 in E flat major, D. 929 [Op. 100] 2nd Movement by Franz Schubert). Director Mastroianni seems to be the one who chose the piece, and its placement as a motif in the episode (interviewed in Wax 2015, 75-6). E: OOOH! Nice catch; that’s brilliant, and thumbs up to Mastroianni! All cool with the setup. But has the series ever fully acknowledged the supernatural existing outside of what cursed objects make happen? Here, there are vampires regardless of the cursed objects’ power. So, what exactly is the mythos or “‘verse” of Friday the 13th: The Series, then? The latter episodes of Season 2 and several episodes of Season 3 thus far seem to be playing fast and loose with the show’s established tropes, with Micki’s occult powers, Ryan’s reversion to a child self, and now the presence of vampires in the show’s reality. And I would find this experimentation more intriguing, I suspect, if any of these ideas were sustained beyond a single episode. Maybe this is the special superpower of the semi-anthology series—to be able to pick up and drop reality-altering ideas for the show without repercussions. I would say that the above hermetically-sealed element includes Jack’s early identification with the vampire’s own compulsion to “hunt,” and his morbid and dark musings at episode’s end about vampires, after he has let one of them live: “I wish I had their wisdom. … They must understand more than we do. God help me, I almost envy them.” We almost invariably see Jack as a support system for the younger set when they have these moments. This kind of deep thoughts moment is usually reserved for Jack’s wise pronouncements. His morbidity here is just not prepared for elsewhere in the series. The Cheese: Okay, let’s talk requisite lesbian vampire makeout scenes. Or let’s not. But here’s a fairly upfront place where the horror series’ luridness meets that of late-night TV. All the big cable/satellite channels at the time—Showtime, The Movie Channel, Cinemax, HBO—had their late-night softcore erotica, and the Playboy Channel (1982-89) was very popular on cable and satellite at this time (it continued on and still exists, rebranded as Playboy TV), and the fact that these scenes made the cut for syndicated TV (Mastroianni expresses surprise that they did) is likely due to a hetero-masculinist sense that homosexuality is okay on TV as long as it’s two women. (Because, of course, they aren’t doing this for themselves; they’re performing for an audience that is presumably heterosexual and male. I certainly can’t imagine the same scene occurring on 1980s TV between two men. They were barely passable in Neil Jordan’s big-budget borefest adaptation of Interview with the Vampire.) Still, these scenes get away from Mastroianni, who seems to think he’s doing cutting-edge work by having women in white lingerie caress and kiss each other in bedrooms that look like they were dressed for the set of a Bonnie Tyler video (lots of flowy netting around the beds). E: And Tyler herself has said “Total Eclipse” was supposed to be about vampires. K: “I’m one of them now,” says vampire Michele to her former fiance (and now captor), Kurt. Now, that statement could “go both ways,” if you know what I mean. I guess Kurt gets the picture, since the “meal” he brings home to his vampire bride is a woman. More specifically, she’s a sex worker he meets while she’s erotically licking an ice cream cone, and whom Mastroianni describes as more “classy” and “innocent,” not “trashy” like the sex workers hand-picked to feed the daughter in the episode “Better Off Dead” (2.15). Anyway, The Hunger (1983) this is not. Hell, this isn’t even Zalman King. (Mastroianni would soon after direct two of the twelve episodes of Dark Shadows: The Revival [1991]). E: Huh. That’s why his aesthetic rings a bell. Yes, I totally watched the Ben Cross version of Dark Shadows. Mock me if you will. K: No mockery here. I very much want to see it. I also like Ben Cross. E: IF you can watch UK DVDs, you can get it cheap on Amazon. K: I can! Curiosities:

One of the things I really liked about this episode was the flying vampires, achieved with a combination of crane shots and SteadiCam, and obviously wires. Even better was the homage at around nine minutes in to Tobe Hooper’s 1979 TV miniseries Salem’s Lot (image below). I wish the episode had sustained this aspect of its narrative rather than the so-called erotics of its main love story. Still, there is much to recommend about this episode, including its cheese factor. And, as I’ve said before about many episodes in this series, it’s drenched in atmosphere and beautifully lit.

ERIN’S THOUGHTS (before reading yours): As per our discussion above, here is yet another entry that seems to be its own thing, instead of part of a bigger picture. My “arc” impulse suggests that somehow this retroactively explains the vampire landlady in “The Baron’s Bride,” but honestly, nothing really explains that and I highly doubt that was their intention. Because, suddenly, there’s a whole community of vampires living in the city? Which they’ve just now discovered and yet have clearly been operating there for decades?

K: Agreed. As I say above, this kind of reinvents the show’s mythos a little too widely. E: Don’t mind me; I’m still annoyed that in the previous episode everyone said “hung” instead of “hanged.” (Because, clearly, that’s the biggest issue with the previous episode.) K: I didn’t notice! I guess I was ‘hanged’ up on those other issues.] Stylistically, this is really well done; clearly they were going for a noir feel: the lighting, the grey morality, and Jack’s be-hatted and be-trenchcoated pensive voice over. Oh, and the sex sax. A few things to note here. There’s a definite shift, likely inspired by Rice, in the highly romanticized/erotically charged interactions between the vampires and humans. Evan, of course, is trying to put the moves on Micki, but it is two drinking scenes, with the first staged/shot to imply a menage a trois, and then Kurt’s “drink me” scene. Also, Micki straight up says that the “objects call out to the users,” which is nice of the show to finally acknowledge. Finally, the “green” eyes effect is used again in Forever Knight a few years later. And yet? This episode reads to me as quite choppy and uncertain as to where it’s going. K: Agreed. E: Kurt’s quest for revenge leads him to dark places, including killing a cop and a priest, which suggests the cross’s firepower is fueled by the stabby bit, and yet once he loses the cross, he’s got no problem becoming what he hates? Jack lets Michele go because? If she doesn’t feed, she’ll die, so it’s not like what Micki suggests at the end: That she can choose to, I don’t know, go vegetarian? K: As a vegan vampire, I can tell you they have some really great ‘blood replacer’ products on the market these days. E: HA! For the discerning bloodsucker! [K: The “ethical vampire”?] Micki runs in to save Kurt and then just stands there? But, perhaps the most egregious: As Jack sits by the water and contemplates these events, he’s not thinking of Kurt and Michele’s tragedy. Instead? “I wish I had their (the vampires) wisdom.” That’s the takeaway? K: LOL, I know. E: Ugh. I think I might be a bit cranky and tired. Kurt’s sin is wrath, while I’m stuck in sloth. |

Critical Rewatch #1Friday the 13th: The Series aired in syndication from 1987 to 1990. It boasts a large fanbase but almost no scholarly commentary. This episode-by-episode critical blog on the series is part of a research project by Erin Giannini and Kristopher Woofter that will include the series in a scholarly monograph on horror anthology TV series in the Reagan era. Archives

July 2021

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed