|

Season 3, Episode 7: “Hate on Your Dial” (Allan Eastman, director; Nancy Ann Miller, writer)

An interesting—if deeply problematic—take on toxic families and the persistence of hate.

KRIS’S THOUGHTS: At its most political, this show is disturbing and important. In this context, this episode is the first from season 3 worthy of discussion at length in our book. It’s equally as political as writer Nancy Ann Miller’s previous effort, “Wedding Bell Blues” (2.22), but dramatically different in tone. It’s also more problematic in what it’s trying to do.

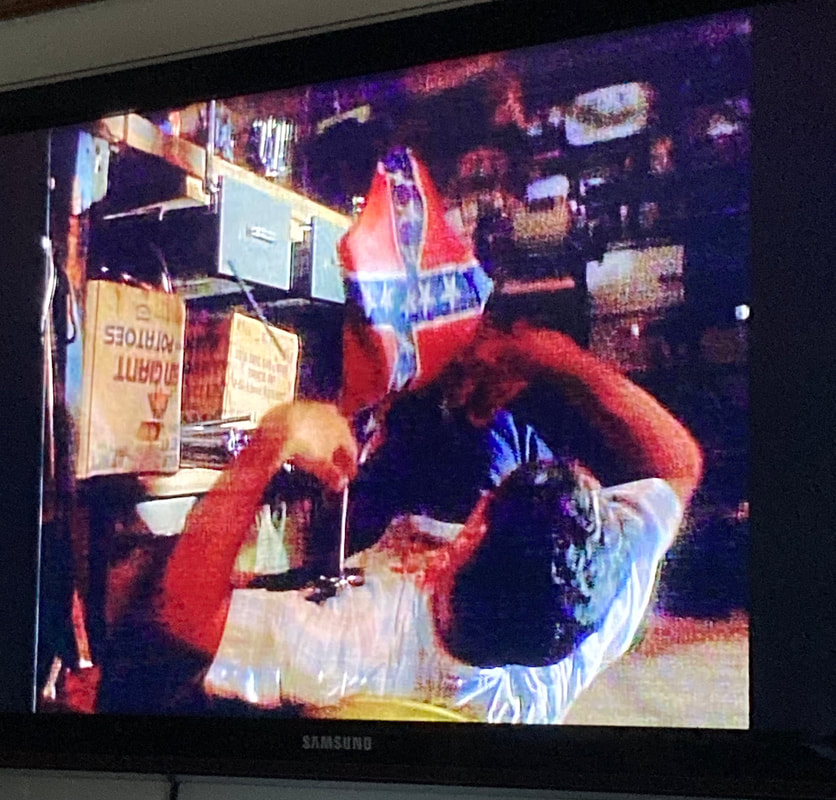

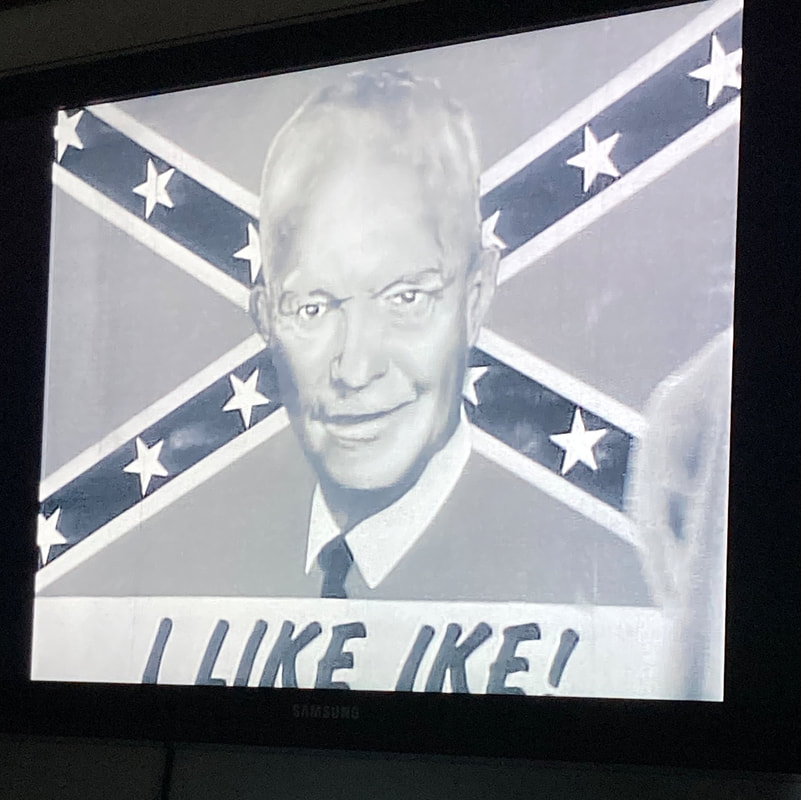

The cold opener features a scene in a garage between brothers Archie and Ray Pierce. Archie is noticeably “slow” (a word used in the script; Johnny’s word for him later is “retarded”), and Ray is noticeably a racist pig, longing for days past in Mississippi when their daddy was in the KKK. Daddy was later hanged for killing a black man, leaving only the two boys and their mother, a young actress wearing old-age makeup, suggesting clearly that this will be a flashback episode. The boys are working on a white 1954 Chevrolet in this scene that will figure pivotally later when Johnny accidentally sells a cursed factory-made ‘54 Chevy radio to Archie (adding in a confederate flag that just happens to be in the Curious Goods shop as a bonus). Curiously (ahem), the radio comes to the shop when a Black woman brings in box of “junk.” for this viewer, at least, the suggestion was that this could be a case where the radio’s “allegiances” are to a cause that is not necessarily that of the owner, which would have made this episode in some ways more trenchant in its investigation of racism. I’ll explain. In the episode “Crippled Inside” (3.4), the so-called benefits of regaining sensation in her body ultimately result in the protagonist’s moral corruption and rather tragic death. In “Hate on Your Dial,” the radio gives Ray what he desires: to return to a time and place where his vicious racism could be more out in the open. (Of course, he could have waited for the Trump era for this.) But the “tragic” ending for Ray—burned at the stake as a spy at a KKK rally by his own father—is inadvertent. Had the radio transported Ray back to 1954 actively as a way to punish him, rather than fulfill his desire to be freer in his hate, the episode might have a different edge in its entirely white-centered narrative. At least, in other words, there would be at least a centering of Black agency in the cursed object itself, which would offset the episode’s problematic discussion of racism’s degenerative effects on white families. The question is, can this episode push past its white-centering? The answer is, unfortunately, no. The script refers to Black Monday, “the day all white folks got in trouble,” possibly a riff on the more typical use of the term to indicate moments of stock market crashes and ensuing economic depressions. And in keeping with the sidelining of this once-mentioned event, we see nothing of the black families affected, just Black victims being persecuted by hooting and yee-hawing white folks. The “tragedy” here is one of how racial hate tears apart white families, and the episode ends with Ray’s father burning him at the stake thinking him a spy, and on the final image of Mrs. Pierce in tears holding the photo of her family. Erin: Yes! Like the previous episode, it’s privileging the wrong pain. K: As he and Jack drive “back to the future,” Johnny’s last line is, “I can’t imagine what it must have been like being black here.” And that is part of the problem: neither can this episode, which doesn’t do anything to center that reality, instead electing to unsettle whiteness. And yet it does unsettle white viewership. An early flashback scene in a diner plays out like a stage, with a Black man touching a white waitress and ensuing violence watched by the white patrons. The white TV viewer will likely feel their own positionality in this uncomfortable scene, but how is a Black viewer meant to be addressed here? Their discomfort comes from being aligned (yet again) with victimhood. The early scene in which Ray torments a kind and friendly young Black kid—making him dance to flying bullets in a basketball court—and then shoots him in the back while he crawls away is an all-too-familiar image, then, now, and in the past. The episode centers the past, but the Rodney King riots are just two years away (29 April to 4 May, 1992). Jim Henshaw, Executive Story Editor for the series, marks this as the series’ best episode, but I would suggest it might instead be the series most exemplary “best intentions” episode. While it handles the subject of racial hate head-on, it fails to situate this experience at all with the perspective of marginalized people, who exist as figures to support a tragic narrative of degenerate whiteness. And yet, taken in the context of the whitewashed, amnesiac, denying Reagan era’s “Morning in America,” the episode is doing some important things. For one, this is the most fucked-up twist on Back to the Future (1985) that I could imagine, and it almost is a critical lesson in what could have been done with that idea instead of revisiting the 1950s as some sort of nostalgia trip. (“Time travel back to a frightening future …” intones the episode promo.) Ray meets his own mother, pregnant with him, and comes to learn that his father’s racial hate is accompanied by acts of violence on his own family. The question of the witness that puts Ray’s father away for murder is never answered, and yet it has to be Ray Pierce’s mother. She’s a silent sufferer in the present, and a silent witness in the past, to discussions of the crime in the family home, and to her husband’s violence with Archie (to stop him from chanting, “Daddy killed a Negro” over and over again). It seems she will act as a witness in part to get him out of the house, and in part due to her conviction that Black folks are “just people like us,” which she says to the grown version of her son, Ray, in the past—again, while he’s gestating in her belly. The fact that Archie in the present narrative is an ally of marginalized folks—telling Ray at one point that he doesn’t like Ray’s violent treatment of his Black friend, Elliott (the boy whom Ray later kills)—is as much an act of resistance to an ideology of hate as his mother’s turning witness against her husband. E: It’s the smallest flash; while Ray is burning, the episode briefly shows what is going on in Steve’s head; he hears Ray saying “there’s a witness” and he sees his wife. He knows who will turn him in. K: In a bit of foreshadowing of similar family violence, at around 29:15, Ray bludgeons Archie to death with a ball peen hammer. As Archie falls to the floor, the confederate flag falls with him. The image (below) would make a compelling screenshot for the book. Another interesting image follows just after, when Jack and Johnny are transported back with Ray to 1954, as Ray rushes to escape the murder scene. As Ray tears off into town, Jack and Johnny stand in the middle of a country road in front of a giant billboard of a smiling Eisenhower backed by the confederate flag and the familiar tagline, “I like Ike.” There are other significant details in the episode that feel rather characteristic of scriptwriter Miller’s previous satirical gifts in “Wedding Bell Blues,” and that undercut some of the episode’s earnest white-centering. One comes in a visual motif that features the town sheriff always sweating. Later, arriving half-heartedly to break up a white protest of Black lawyer Henry Emmett’s efforts to bring justice, he also mentions the sweltering heat. For all his confidence and bravado, he’s “sweating it.” Everything the sheriff says to Emmett as he quells the protest reads like a warning, something Emmett confronts him with. It comes as no surprise, then, when later a captured Jack observes that one of the KKK members has the same shoes as the sheriff. In another such detail, following the protest, the moment where Jack’s friendly warning to Emmett ends in his being thought of as a KKK member is on point: “Thank you, sir,” says Emmett. “I have to say that I’ve never been intimidated so politely.” At least the script doesn’t let Jack come off as a white savior. In a later scene in the final 1954 segment, Ray comes in after Archie has been beaten by his father, and he doesn’t even ask until well into the conversation while Archie is on his mom’s lap badly injured. Here is Ray, after having killed his own brother in the present, looking upon him, brutalized and abused in the past, by a father that will later burn Ray himself at the stake, Ray pleading, “Daddy don’t!,” as his face burns off. E: What’s even worse? He HEARS Archie being beaten and actually fucking shrugs and drives off. BURN HIM.

ERIN'S THOUGHTS (before reading yours): Well, this was brutal to watch, although it taps into what went fairly unacknowledged at the time this aired; the Boomer second wave, of which Ray would be a part, were frequently just like him. (Witness, as per example, Randall Terry, the guy who started Operation Rescue.) These are the Boomers that missed out on the economic boom of the 60s and came of age in the 1970s. They generally were super pissed off and blamed everybody except the ones that were actually responsible. Ray fits this mode quite well.

(The episode also takes a page from, in my view, The Twilight Zone movie section “Time Out,” particularly the fate of the bigoted “time traveller”.) K: Interesting. The ill-fated one with Vic Morrow? There is also a segment of Rod Serling’s Night Gallery that does this kind of thing better than anything I’ve ever seen on television, before or since.] E: Oooh, want to see! And yes, the Morrow one. K: It’s in the series pilot, the last segment, called “The Escape Route,” about a Nazi in hiding in South America. E: I found this episode extremely difficult to watch. The whipping/beating scene went on for too long; I had to fast forward. There is a line—at least for me—between what serves the narrative and what becomes gratuitous. The mention of Roots in the episode is instructive; having aired maybe 10 years earlier, and containing scenes of abuse such as were shown here. At the time, that was groundbreaking, and given that Alex Haley wrote the source material based in part on his own family history, it has a different resonance. Because the episode stays firmly in the point of view of the white characters (even those with good intentions), the violence it shows becomes even more problematic; we don’t get the perspective of the victims at all. Even the fact of having Archie be a stand-in for the other marginalized people (and hands-down the most sympathetic white character) doesn’t quite push it into “white savior” territory, but still privileges the white perspective in a story about racism. K: On point. E: There are some things that this episode absolutely nails. One, that you can’t tap into that rage and expect it’s not going to be enacted against anyone who gets in your way. While this seems obvious, clearly the writer understood the psychology of that time of person well enough to show that no one was safe from it; poor Archie. Even better? Unlike “The Shaman’s Apprentice”, when Henry Emmett (that last name cannot be accidental) tells Jack that it was the most “polite” intimidation he’d gotten, Jack’s first instinct ISN’T to try and “not all white people” him. He reads the time and the situation exactly right; there is no way that Jack, no matter his intentions, can communicate that information to Henry without it sounding like intimidation. K: Agreed. And, funny that the same humility and comprehension could be given to an Indigenous person in “Shaman.” E: That the sheriff was complicit was expected; that he was in the Klan and responsible for burning Ray and attempting to do the same to Henry was a bit of a turn. (Not sure this qualifies as a plot hole, but if the sheriff is in the Klan and is himself guilty of murder, how did Steven ever come to trial, never mind being convicted and hanged?) The constant use of the word “boy” directed at African American men of all ages. Finally, that racism isn’t “solved” or a product of the past. “The future isn’t much more comforting.” Jack, you’ve no idea. K: It’s quite a different voice here from Ryan’s notion in “Eye of Death” (2.13) that “in my time, no one thinks badly of” the confederacy. And yet, that these two statements can come in the same series suggests a very messy and unformed series politics, mostly conservative with the occasional blip of subversion and critique. This episode is almost a capsule of the rest of the series in that respect. E: This, I think, is a significant issue with the anthology/semi-anthology format overall, and the era. Excepting Lear and MTM Productions, the era of the “showrunner” was more than a decade later. There’s no real sense of this as a “Mancuso” production, so it is the writers/directors who set the narrative and visual tones, rather than having an overarching POV that is typical of showrunners now. Add that to the lack of a strong arc and it makes it indeed makes it messy and hard to pin down. K: This makes me think it might be a good idea to take a look at the most truly subversive episodes, and locate the more critical voices (writers, directors) on the show. We could even do a separate list of top ten “most subversive/political/edgy” episodes. I’m not sure this one would make the cut, solely for its white-centering narrative. We could make a “Nice try” list to compliment it! E: I LOVE every part of that idea. I think it makes the most sense in approaching these types of shows; it should have occurred to me before, but I’ve gotten so used to that particular paradigm that it didn’t. Not to veer too far off, but Caldwell’s Televisuality is a good read for this, particularly when he talks about the zero-style aesthetic of TV in the 1970s which prized the writing/acting over the visuals. It’ll take some digging, I think, but I think focusing on individual writers/directors is already kind of baked into what we’ve done here. I also was surprised by some of the plot turns. I’d figured out that Margaret was probably the witness about the halfway mark, and figured that might be a turning point for Ray. Instead, he never figures it out, and dies horribly. (Am I sad about that? No. Does it trouble me that it doesn’t make me sad? A little. K: It’s hard to be sad because the episode’s centering of whiteness is so troubling, you feel like you’re forgetting to be outraged by that, if you’re sad for Ray. E: That Steven was responsible for what happened to Archie also surprised me, and the way in which Ray mythologized his father would lead where it did was exactly right in terms of his character. The way this episode resonates with what’s happening today makes it a chilling watch, from the mythologizing of the past to the fact that the “radio” is a conduit to enacting hate is a subtle touch from a show that’s rarely subtle. K: Interesting, yes. And connects to “The Butcher” (2.19) with its radio show, and, to a lesser extent, “And Now the News” (2.3). The radio gets a lot of “airtime” on this series. I’m about to watch “Spirit of Television” (3.18), so we’ll see where that one takes us.]

Season 3, Episode 8: “Night Prey” (Armand Mastroianni, director; Peter Mohan, writer)

The introduction of a community of vampires plays fast and loose with the show’s mythos, pushing this one into backdoor pilot territory.

KRIS’S THOUGHTS: In this episode’s cold opener, a pensive, melancholic Jack sits on a boardwalk bench at night, musing on the blurring of distinctions between good and evil (his words are quoted in full in Wax [2015, 370]). It’s a scene in keeping with the times, with the romantic vampire popularized by Anne Rice (1976) now at the height of its popularity. The decade began with John Badham’s (1979) sexy Dracula played by Frank Langella, and the TV series Cliffhangers’ (1981) Dracula played by Michael Nouri. And Interview with the Vampire (1994) was soon to come. Intimations of Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003) come as well with much of the action taking place in a post-industrial warehouse space where vampire hunter Kurt has holed up in an attempt to reclaim his fiancee, kidnapped and turned years before in 1969 by hot vampire Evan Van Hellier (A vampire stole my bride!).

Bonus note on the cold opener (and one later scene): Conventional populism would suggest the opening scene of two ill-fated lovers being stalked by a vampire be underscored by Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata”; yet, here, a pleasant surprise comes in the use of music used by Stanley Kubrick for a morose ending scene in Barry Lyndon (1974) (it’s Piano Trio No. 2 in E flat major, D. 929 [Op. 100] 2nd Movement by Franz Schubert). Director Mastroianni seems to be the one who chose the piece, and its placement as a motif in the episode (interviewed in Wax 2015, 75-6). E: OOOH! Nice catch; that’s brilliant, and thumbs up to Mastroianni! All cool with the setup. But has the series ever fully acknowledged the supernatural existing outside of what cursed objects make happen? Here, there are vampires regardless of the cursed objects’ power. So, what exactly is the mythos or “‘verse” of Friday the 13th: The Series, then? The latter episodes of Season 2 and several episodes of Season 3 thus far seem to be playing fast and loose with the show’s established tropes, with Micki’s occult powers, Ryan’s reversion to a child self, and now the presence of vampires in the show’s reality. And I would find this experimentation more intriguing, I suspect, if any of these ideas were sustained beyond a single episode. Maybe this is the special superpower of the semi-anthology series—to be able to pick up and drop reality-altering ideas for the show without repercussions. I would say that the above hermetically-sealed element includes Jack’s early identification with the vampire’s own compulsion to “hunt,” and his morbid and dark musings at episode’s end about vampires, after he has let one of them live: “I wish I had their wisdom. … They must understand more than we do. God help me, I almost envy them.” We almost invariably see Jack as a support system for the younger set when they have these moments. This kind of deep thoughts moment is usually reserved for Jack’s wise pronouncements. His morbidity here is just not prepared for elsewhere in the series. The Cheese: Okay, let’s talk requisite lesbian vampire makeout scenes. Or let’s not. But here’s a fairly upfront place where the horror series’ luridness meets that of late-night TV. All the big cable/satellite channels at the time—Showtime, The Movie Channel, Cinemax, HBO—had their late-night softcore erotica, and the Playboy Channel (1982-89) was very popular on cable and satellite at this time (it continued on and still exists, rebranded as Playboy TV), and the fact that these scenes made the cut for syndicated TV (Mastroianni expresses surprise that they did) is likely due to a hetero-masculinist sense that homosexuality is okay on TV as long as it’s two women. (Because, of course, they aren’t doing this for themselves; they’re performing for an audience that is presumably heterosexual and male. I certainly can’t imagine the same scene occurring on 1980s TV between two men. They were barely passable in Neil Jordan’s big-budget borefest adaptation of Interview with the Vampire.) Still, these scenes get away from Mastroianni, who seems to think he’s doing cutting-edge work by having women in white lingerie caress and kiss each other in bedrooms that look like they were dressed for the set of a Bonnie Tyler video (lots of flowy netting around the beds). E: And Tyler herself has said “Total Eclipse” was supposed to be about vampires. K: “I’m one of them now,” says vampire Michele to her former fiance (and now captor), Kurt. Now, that statement could “go both ways,” if you know what I mean. I guess Kurt gets the picture, since the “meal” he brings home to his vampire bride is a woman. More specifically, she’s a sex worker he meets while she’s erotically licking an ice cream cone, and whom Mastroianni describes as more “classy” and “innocent,” not “trashy” like the sex workers hand-picked to feed the daughter in the episode “Better Off Dead” (2.15). Anyway, The Hunger (1983) this is not. Hell, this isn’t even Zalman King. (Mastroianni would soon after direct two of the twelve episodes of Dark Shadows: The Revival [1991]). E: Huh. That’s why his aesthetic rings a bell. Yes, I totally watched the Ben Cross version of Dark Shadows. Mock me if you will. K: No mockery here. I very much want to see it. I also like Ben Cross. E: IF you can watch UK DVDs, you can get it cheap on Amazon. K: I can! Curiosities:

One of the things I really liked about this episode was the flying vampires, achieved with a combination of crane shots and SteadiCam, and obviously wires. Even better was the homage at around nine minutes in to Tobe Hooper’s 1979 TV miniseries Salem’s Lot (image below). I wish the episode had sustained this aspect of its narrative rather than the so-called erotics of its main love story. Still, there is much to recommend about this episode, including its cheese factor. And, as I’ve said before about many episodes in this series, it’s drenched in atmosphere and beautifully lit.

ERIN’S THOUGHTS (before reading yours): As per our discussion above, here is yet another entry that seems to be its own thing, instead of part of a bigger picture. My “arc” impulse suggests that somehow this retroactively explains the vampire landlady in “The Baron’s Bride,” but honestly, nothing really explains that and I highly doubt that was their intention. Because, suddenly, there’s a whole community of vampires living in the city? Which they’ve just now discovered and yet have clearly been operating there for decades?

K: Agreed. As I say above, this kind of reinvents the show’s mythos a little too widely. E: Don’t mind me; I’m still annoyed that in the previous episode everyone said “hung” instead of “hanged.” (Because, clearly, that’s the biggest issue with the previous episode.) K: I didn’t notice! I guess I was ‘hanged’ up on those other issues.] Stylistically, this is really well done; clearly they were going for a noir feel: the lighting, the grey morality, and Jack’s be-hatted and be-trenchcoated pensive voice over. Oh, and the sex sax. A few things to note here. There’s a definite shift, likely inspired by Rice, in the highly romanticized/erotically charged interactions between the vampires and humans. Evan, of course, is trying to put the moves on Micki, but it is two drinking scenes, with the first staged/shot to imply a menage a trois, and then Kurt’s “drink me” scene. Also, Micki straight up says that the “objects call out to the users,” which is nice of the show to finally acknowledge. Finally, the “green” eyes effect is used again in Forever Knight a few years later. And yet? This episode reads to me as quite choppy and uncertain as to where it’s going. K: Agreed. E: Kurt’s quest for revenge leads him to dark places, including killing a cop and a priest, which suggests the cross’s firepower is fueled by the stabby bit, and yet once he loses the cross, he’s got no problem becoming what he hates? Jack lets Michele go because? If she doesn’t feed, she’ll die, so it’s not like what Micki suggests at the end: That she can choose to, I don’t know, go vegetarian? K: As a vegan vampire, I can tell you they have some really great ‘blood replacer’ products on the market these days. E: HA! For the discerning bloodsucker! [K: The “ethical vampire”?] Micki runs in to save Kurt and then just stands there? But, perhaps the most egregious: As Jack sits by the water and contemplates these events, he’s not thinking of Kurt and Michele’s tragedy. Instead? “I wish I had their (the vampires) wisdom.” That’s the takeaway? K: LOL, I know. E: Ugh. I think I might be a bit cranky and tired. Kurt’s sin is wrath, while I’m stuck in sloth.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Critical Rewatch #1Friday the 13th: The Series aired in syndication from 1987 to 1990. It boasts a large fanbase but almost no scholarly commentary. This episode-by-episode critical blog on the series is part of a research project by Erin Giannini and Kristopher Woofter that will include the series in a scholarly monograph on horror anthology TV series in the Reagan era. Archives

July 2021

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed